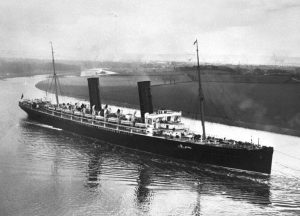

The steel steamship Campania was built at Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Co Ltd, Glasgow (Yard No 364) and launched on 8th September 1892. She measured 601.0′ x 65.2′ x 37.8′ and her tonnage was 12950 gross tons, 4974 net tons. Built for Cunard her twin 5 cylinder vertical triple expansion engines generated 500 registered horse power making her a fast and popular ship. She entered service for the company in 1894 after almost a year fitting out. She was a beautiful ship sailing mainly on the Liverpool/New York route. In 1901 she became the first Cunarder to be fitted with the new device from Marconi – a wireless and for a time she held the Blue Riband award for the fastest crossing of the North Atlantic route. Obsolete by October 1914 she was sold to ship breakers T W Ward for scrapping but the outbreak of Word War I was to provide her with a new lease of life when she was saved from the breakers and requisitioned by the Royal Navy.

The Navy purchased Campania from the ship breakers on 27th November 1914 for £32,500, initially for conversion to an armed merchant cruiser. However in a change of plan the ship was converted by Cammell Laird to an aircraft carrier and a 160-foot flying-off deck was added. Cranes were fitted on each side to transfer seaplanes between the water and the holds. The midships hold had the capacity for seven large seaplanes and the forward hold, underneath the flight deck, a further four small seaplanes, but the flight deck had to be lifted off the hold to access these airplanes.

HMS Campania was commissioned on 17th April 1915. The first take off on the 6th August was a dramatic one when a Sopwith Schneider, mounted on a wheeled trolley, managed to take off from Campania while the ship was steaming into the wind at 17 knots. The Sopwith aircraft was the lightest and highest-powered aircraft in service but barely managed to take to the skies in the favourable wind showing that heavier aircraft could not be launched from the short flight deck.

By October 1915 Campania had exercised with the Grand Fleet seven times, but had only launched aircraft three times as the North Sea was often too rough for safe use of her seaplanes. Her captain recommended that the flying-off deck be lengthened and given a steeper slope and the ship was accordingly modified at Cammell Laird between November 1915 and early April 1916. The forward funnel was split into two funnels and the flight deck was extended between them and over the bridge to a length of 245 feet. A canvas windscreen was provided to allow the aircraft to unfold their wings out of the wind, and a kite balloon and all of its supporting equipment were added in the aft hold. Campania now carried seven Short Type 184 torpedo bombers and three or four smaller fighter’s. A Type 184 made its first takeoff from the flight deck on 3rd June 1916, also using a wheeled trolley. This success prompted the Admiralty to order the world’s first aircraft designed for carrier operations, the Fairey Campania. The ship received the first of these aircraft in late 1917 where they joined smaller Sopwith 1/12 Strutter scouts.

Campania departed Scapa Flow on 30th May 1916 en route to the Battle of Jutland but she was ordered to return to Scapa Flow as she lacked an escort and German submarines had been reported in the area. Subsequently she ship participated in some anti-submarine and anti-Zeppelin patrols, but she was later declared unfit for fleet duty because of her ageing machinery and she became a seaplane training and balloon depot ship.

Late in October of 1918 the Germans requested an Armistice and, although it was not actually signed till 11th November, the war was effectively over. At the time HMS Campania was stationed in the Forth with a number of other large capital ships – HMS Glorious, HMS Royal Oak and HMS Royal Sovereign. On the night of 4th November all four ships were lying at anchor off Burntisland, Fife. Aboard Campania, Captain John J C Lindsay RN was in his cabin and Lieutenant Thomas Smart RNR was the Officer of the Middle Watch.

The evening was dark but calm with only the occasional gust of wind. Earlier that evening, a report of possible bad weather had been issued by the Edinburgh Meteorological Office and had been passed to Captain Lindsay but he took no special precautions. At around 03:00 the wind rose from the south and soon a force 4 – 5 wind was pulling the huge ship against its single anchor chain – she had 75 fathoms of chain out which was still more than enough to cope with the conditions. However the barometer continued to fall until, at around 03:25am, a violent squall swept over the anchorage instantly increasing the wind to a force 10 for a few minutes. The squall struck the Campania or her starboard beam and she immediately began to drag. Lieutenant Smart quickly raised the alarm calling the officers to the bridge and turning out an anchor watch. At the subsequent enquiry he was criticised for not attempting to release the second anchor himself – an action which might have saved the ship. When Captain Lindsay arrived on deck he did order the second anchor let go in an attempt to arrest her progress.

By this time, the Campania was drifting north east and ever closer to HMS Royal Oak. At 03:35am, ten minutes after the squall struck, the Campania smashed against the sharp bow of the Royal Oak. The bow tore into the side of Campania holing her on the port side at the dynamo compartment. The crew were at action stations by this time and the watertight doors around the damage were rapidly sealed off. The flooding of the dynamo room quickly caused power failure throughout the ship but, thankfully, the emergency system surged into action and light was restored. The captain ordered the first distress signal to be sent by visual at 03:55am and by wireless at 04:09am to the Commander in Chief, Coast of Scotland. These signals were repeated at 04:39am. “Urgent. Am making water rapidly. Assistance urgently required”. Interestingly, the signals did not reach the King’s Harbourmaster’s Office until 05:00am and, worse still, the salvage steamer Mariner, moored only a few miles away at Leith, did not receive any instruction to assist until 07:00am – by this time it was too late although it is doubtful if she could have done anything to avoid the sinking. An inspection below soon revealed that the ship was in serious difficulties and, despite the closing of the watertight doors around the damaged area, the port engine room was also flooding. The engine room bilge pumps were started but the water continued to rise quickly. The Campania was beginning to list to port – to bring her upright the watertight door between port and starboard engine rooms was opened to balance the flooding which did work for a time.

Outside, the Campania was still adrift and, now with the Royal Oak attached and dragging her own anchor, heading towards the next ship in line – HMS Glorious. Both ships fouled the Glorious shortly afterwards. The Royal Oak struck the stem of Glorious and dragged along her starboard side but, thankfully, little damage was done. The Campania freed herself from the Royal Oak but smashed into the port side of Glorious slewing round so that he bow now pointed west parallel to Glorious. All three vessels were now adrift and heading for the fourth in line – HMS Royal Sovereign. By this time the anchorage was alive with tugs – Neptor, Sun VII, Merimac, Malta, Volcano were joined by the salvage ship Mariner and by the destroyer HMS Grenville but there was little they could do to help. Grenville and one of the tugs began to take off the Campania’s crew. At around 06:00am Rear Admiral Sir Richard Phillimore KCMG arrived alongside Campania and boarded her. He took charge of the sinking ship but by now it was too late. He considered an attempt to tow her to the shallows off Burntisland but decided against it as, by now, she was very low in the water, would have been almost impossible to control and he anticipated that she would probably sink in the fairway. Both Glorious and Royal Oak managed to get up steam and moved aside but Campania, with her engine-rooms now flooded, drifted on past Royal Sovereign until, at around 08:35am, some five hours after the squall that destroyed her and with all her crew now safely onto other ships, she sank by the stern some seven cables east of Royal Sovereign. She sank upright and, as calm returned to the anchorage, came to rest with her funnels and masts above water.

The first Court of Enquiry into the loss of Campania, held aboard HMS Repulse was led by Vice Admiral Oliver, Commander of First Battle Cruiser Squadron with the captain’s of HMS Renown and HMS Princess Royal attending. Captain John Lindsay was cleared of blame for the loss but Lieutenant Smart was criticised for failing to try to drop a second anchor immediately he discovered she was adrift. However, it appears that this opinion was later overturned as, a few weeks later, a charge was made against Captain Lindsay. At his subsequent Court Martial aboard HMS Erin he was held responsible for the loss of his ship as, they felt, he had failed to take adequate precautions to cope with potential bad weather highlighted in the report from Edinburgh by setting an anchor watch and getting up steam. He was also criticised for failing to organise the closing of watertight doors in other parts of the ship further from the damage as, once the water escaped past the closed doors, it then spread rapidly throughout the rear end of the ship which hastened her final sinking.

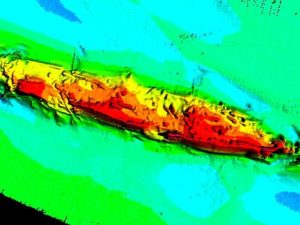

The wreck, which lay close to the fairway, was clearly a danger to shipping and a number of attempts were made to disperse her. After the first, carried out in 1921 by a Sunderland firm, the wreck buoy was removed but the buoy was replaced in 1941 as it was deemed in a survey of that date that some danger to shipping still existed as the least depth was only 5 fathoms. Some additional dispersal work in 1947 which took the clearance to more than 7 fathoms allowed the buoy to be removed again in 1948. The wreck was heavily salvaged in the 1960s but there is still a substantial amount of wreckage remaining, reported to be in two large pieces, at 56°02.406’N, 003°13.511’W lying in 25 metres of water. The jumbled wreckage is spread over a huge area of the seabed extending almost 200 metres by 25 metres and at some points rises more than 8 metres from seabed.